Lieutenant Tom Marsh (1923 - 2016)

Tom Marsh was born in Australia, but moved to England in 1930 after the death of his father who had been an Officer in the British Indian Army. In 1934 the family moved to the Purlieu in Upper Colwall. What follows are the recollections that Tom wrote about his time with the Royal Engineers (RE) during World War 2.

Personal Recollections

After the outbreak of WW2 it was inevitable that I would join the Army on leaving Wellington College, but to which branch? For academic reasons my tutor advised that I should join the Royal Artillery, but I insisted on the Royal Engineers (RE), because it would be constructive, not destructive. His advice was well justified, but I have no regrets that I disregarded it. I was accepted by RE to attend Cambridge University for six months before starting military training. Later in training, in a wild moment, which I certainly don't regret, I volunteered to join Airborne Forces. I was accepted and when commissioned on 1 May 1943 I joined 3 Para Squadron RE, part of 6th Airborne Division, which was being formed in preparation for D Day - whenever that might be.

I did my parachute training at Hardwick Hall and then on to Ringway Airfield (now Manchester Airport). Initially we jumped from Whitley bombers in "sticks" of ten, an officer in each aircraft. It was not until early in 1944 that we started to use Dakotas which carried 20 parachutists. By the time D Day approached 3 Para Sqn RE was extremely fit, confident and ready for anything. Our motto was "Go to it". We did. Our average age was 21, I was the youngest officer in the squadron. The unit achieved all its objectives on D Day, dropping 50 minutes after midnight. Our Squadron casualties were lighter than expected, but our battalions in Normandy suffered heavily.

27 May - 6 June 1944

I am in a tent in a small field beside the road between Cirencester and Cricklade. We arrived here on 27 May following the inspection of my brigade, 3 Parachute Brigade, by King George 6th following that by Field Marshal Montgomery. Our field is packed with tents. We are under strict supervision the whole time. Though not casually apparent from the road, the hedges are covered by sentries with loaded rifles and Bren guns. Anyone approaching too close to a hedge is to be shot and questioned only afterwards. There are also posters "To speak of troop movements - Penalty: Death to your Comrades". This is the pre Operation Overlord Transit Camp allotted to 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion Group of the 6th Airborne Division.

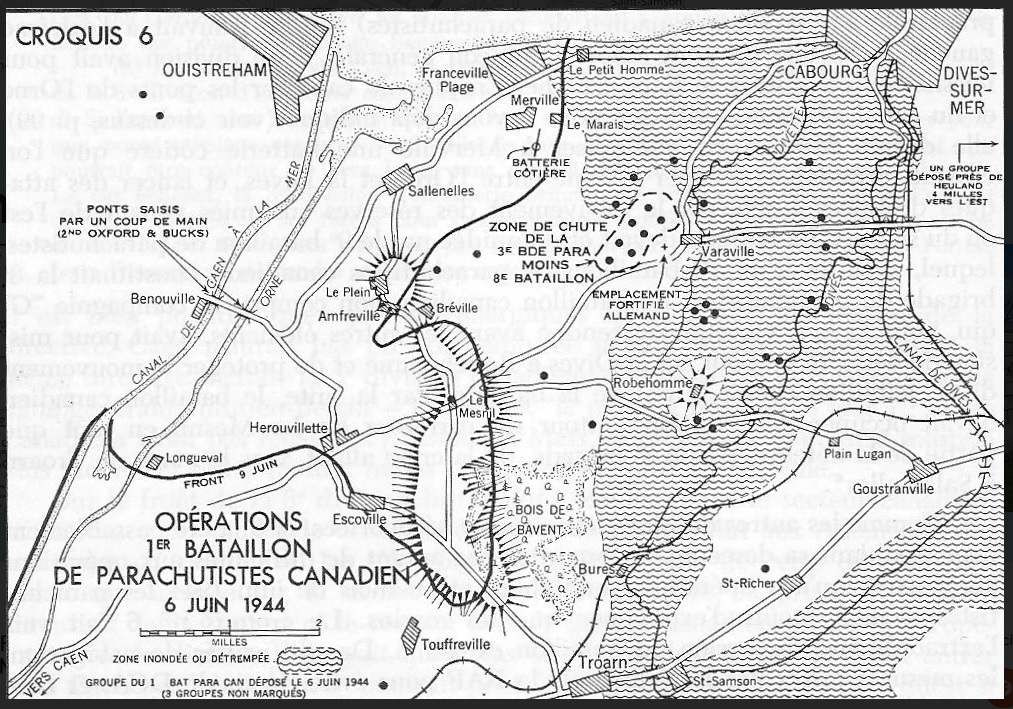

On 28 May the Briefing Tent opened to officers. The model is as near perfect as months of labour can make it. The detail is incredible. There are scale models of our bridges. The Divisional task is the capture and occupation of the high ground on the left flank of the Normandy Landings, east of the River Orne and the capture of the bridge at Ranville, intact. My squadron of the Royal Engineers is responsible for blowing up five bridges over the River Dives, some 5 miles further East. I am the most junior of five officers in my troop (overall strength 40). My troop's particular target is a larger version of the one in the grounds of Canford School, which we have practiced attaching explosive charges to ad nauseam. There is a vast model of the whole area supplemented by detailed maps, plans of defences and air photos for miles around. The atmosphere in the room is not tense.

Outside our men are sunbathing and chatting. Cricket, softball, netball and badminton are somehow all being played simultaneously in an area only the size of two tennis courts. All without fuss. A Tannoy system plays music interrupted by the odd announcement. If you close your eyes, it sounds almost like a fairground. From the road we look a rather idle, happy go lucky lot. Convict haircuts are the order of the day. Some choose to be wholly bald, some have left just three dots and a dash and one section of Canadians has the letter each of the word VICTORY. They are getting much press attention. There is not a drop of alcohol in the camp.

By 3 June all ranks had been briefed. Everything has been repeated at least 20 times. We should remember every word. There is now a definite change from "dreamland" to reality. We have great confidence in our Canadians. Talking to them is a tonic. They just can't help being funny, even if they don't mean to be.

The 5th of June was a lovely day. In the morning, we loaded our containers again and then a Church service was held. Because it was so hot in the afternoon, small groups at a time were allowed to swim in one of the large ponds across the road. Another was being used by children and their parents. The bank between the ponds was guarded by a greater number of officers in a close chain. There was absolutely no communication. Clothing and equipment is being packed and repacked. Quite apart from our parachutes we are going to drop carrying over 100 lbs each. We will only be able to waddle to and enter our aircraft. My section consists of Ginge Thomson, married a year, looks dismal, a pessimist but a good soul. Corporal Doyle, not very bright, tall, lean and a good sapper. Lance Corporal Devine, just 20, in the Army a year, very strong and game for anything, you can hardly see him for equipment. Sapper Loomes, married with a son a month old, a patient and hard worker. Sapper Aylard, the opposite, thinks in terms of football and cigarettes, always a half smoked one behind his ear. Sapper Malmsjo, half Swedish, just married, always sees the amusing side. Sapper Humphries, a bit of a know all, a good tradesman; very Welsh, always losing his kit. I had learned to look after myself. Everything is well planned, and everyone is confident of success. We have tried to think of every eventuality. Everyone is going about, so far as possible with a smile. There is continuous chatter, but no-one is really listening. I "posted" my last letter home at teatime. "Tea" is going to be late because it is the last meal for some time.

After tea, which was a good meal, we carried all our kit to the parade ground. Each of us was a walking arsenal. Before moving off to the airfield we were addressed by our Officer Commanding (OC) and the Supreme Commander's Order of the Day was read out. We then boarded a lorry, one to each aircraft load, and on arrival at our airfield we scrambled aboard, laden, aided by our crew.

Over 3000 aircraft had been massed in support of the UK and US airborne landings. We took off just before 11 pm on 5 June and jumped at 50 minutes after midnight. This was just 6 hours before the beach landings, which were to be preceded by heavy naval and air bombardment of the coastal defences starting soon after dawn. Only the Coup de Main party, to capture the Ranville bridges over the River Orne, and some pathfinders were dropped ahead of us.

The Brigade was meant to drop onto three relatively flat and open Dropping Zones. In the event there were as many dropped off as on these DZs - and not always on the right one. Some were dropped as far as 32 miles away. The Germans had deliberately flooded the banks of the River Dives, which runs parallel to and the other side of the Le Mesnil Ridge between the rivers Orne and Dives. This ridge was wooded or made up of small fields with thick hedges. My section and another were tasked with destroying the bridge over the River Dives near Robehomme and the rest of the troop the bridge at Varaville.

It was a moonlit night, and the sky was full of aircraft. We crossed the anti-aircraft defences with evasive action at 2000 ft and then dropped sharply to 800 ft to start the drop. Our aircraft stick of sixteen men was led by another officer, and I was last out. Because of the instability of the aircraft while we were standing up and because we were so heavily loaded we were slow to leave the aircraft; so we were stretched out in a long line on reaching the ground, with our containers filled with explosive in the middle. The drill was to rendezvous back at the containers and set off to our objective as soon as possible. There was much to do between jumping and landing in less than a minute. I realised that I was not dropping on the drop zone, there were too many trees. And then I landed on the roof of an isolated cottage and bounced off the roof - out of control to the ground, in far from elegant style, but not much hurt. The noise I made alerted the housewife. Taking me for an interloping German, she gave me an irate earful.

Dazed as I was, I jumped for cover, to collect my wits and equipment, but it was an unwise move because the ditch was deep and full of water. It was not a good start. And, most importantly, I had lost the direction along which we had dropped. I was in an "orchard", rather than an open area. I could hear no other parachutist, only some machine gun fire not far away. I must have lost some time at some stage because by the time I had fallen in with another sapper and we had located our containers, they were empty and the rest had departed towards Robehomme. I judged it useless to set off there and started towards Le Mesnil where my Squadron was concentrating after completing our demolitions.

It was soon daylight, and the surroundings were beautiful on a warm and sunny morning. Soon we joined with other stragglers, and we decided exactly where we were. The RAF fighters were very active above us. We all carried a small bright yellow triangle to identify ourselves. But, as we discovered, this was no sure protection. Not long afterwards we fell in with a larger party, led by our Brigade Commander, which had suffered severely in this way. By this time, the thunderous bombardment of the coastal defences was in full swing, soon followed by the landings. There was firing on our side of the ridge too. We passed several groups of horses grazing in fields most peacefully. What a contrast.

We reached Le Mesnil about midday without running into any Germans. There we were sharply reminded of the cost of its capture by the bodies of Canadians killed, but as yet unburied. The Canadian Battalion was directly responsible for the defence of the ridge in that immediate area. We started digging-in on the verge of the road along the ridge. The Canadian front line was roughly along the hedge, 100 yards in front of us, and the Germans were some 200 yards ahead of that. We were soon under mortar fire.

Brigade headquarters was 100 yards behind us and alongside them was 224 Para Field Ambulance. Le Mesnil was an increasingly unpeaceful and unhealthy place so to be so near such excellent medical support was most reassuring. A high proportion of that unit were conscientious objectors but were highly respected. We only had very light artillery and, to provide heavier support, we had a battleship offshore with 16-inch guns. The rounds had a very low trajectory. They made a strange noise passing close overhead but were most effective.

As German reinforcements built up, so the pressure on 6th Airborne Division and the Commando Brigade holding the ridge increased. On 12 June they all but broke through in the area of Breville and we were moved there hastily to form a last line of defence. There were heavy casualties on both sides, but Breville was recaptured.

During the three months 6th Airborne Division was in Normandy, two of my section were killed. 3 Parachute Squadron Royal Engineers suffered some 20% casualties and the Canadian Battalion some 50%, both casualties of all ranks. Our Officer Commanding was deservedly awarded an immediate Distinguished Service Order (DSO) and four other officers were awarded Military Crosses. Our unit strength was only fifty. All our D Day objectives were achieved, though not quite as planned. The (5) /6th of June 1944 was indeed a long day.

After D-Day

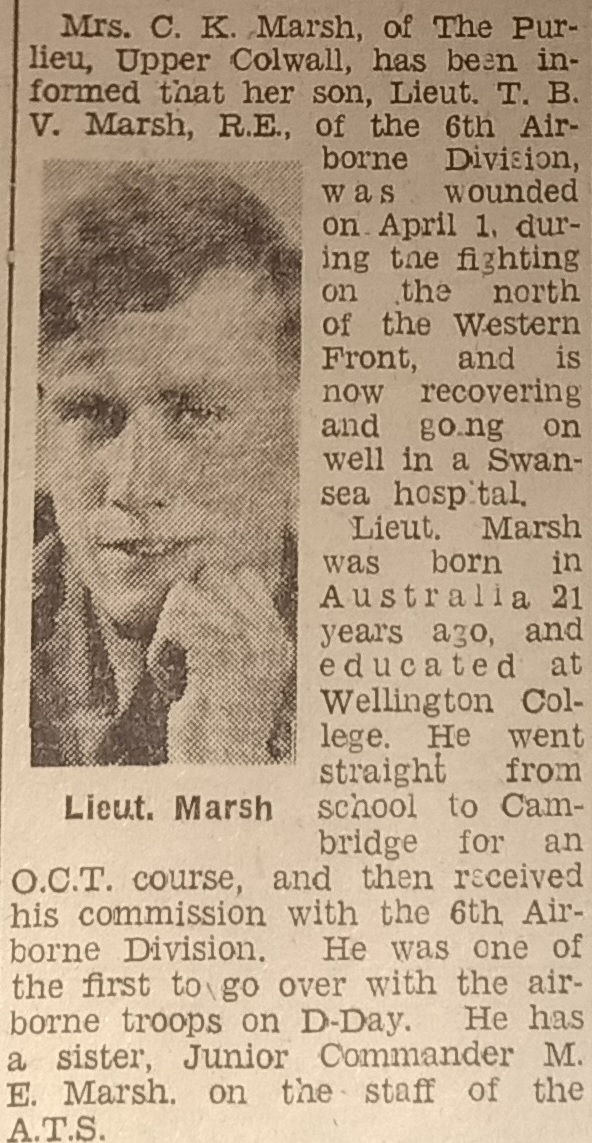

3 Para Squadron unexpectedly moved over Christmas to counter the German invasion of the Ardennes. It was bitterly cold, and we suffered casualties lifting frozen mines. After a month, we moved to opposite Roermond for a short time before returning to the UK to prepare for the Rhine Crossing. Because of a shortage of aircraft, my troop travelled by land incognito, however we joined up well before our advance East began. Our advance was rapid and at dawn, just East of the Dortmund Ems Canal, we found that a German antiaircraft unit was still occupying the farm 500 yards up the road. They fired first. In our attack I was slightly wounded, after which the Germans surrendered. I was evacuated to the UK the same day. 3 Para Squadron RE was among the first British units to join up with the Russians, near Wismar. One of our sergeants, ex Great Western Railways, drove a train there carrying our infantry over the last few miles. The exploits of our Squadron in preparation for D Day on to VE Day were later serialised in the Royal Engineers Journal.

Our Parachute Brigade Group was needed in the far East for the attack on Singapore and moved to India in July 1945, not a pleasant prospect. I was due to fly to rejoin them on what turned out to be VJ Day. At the end of the day the flight was cancelled and I was posted to 286 (Airborne) Park Squadron, Royal Engineers, in the reorganised 6th Airborne Division. This moved to Palestine in September to help maintain internal security there. Our squadron's role was to provide our units with engineering stores, plant and workshop facilities as well as other engineer support required.

After the war, Tom remained in the military until his retirement in 1978, with postings which included Cyprus, Singapore, Germany and Malta. He reached the rank of Lieutenant Colonel and was awarded an OBE for his work with the Royal Engineers in Malta. In 1970, he returned to live in Colwall in the house on the Purlieu where he had grown up.

Postscript from the Marsh Family

Tom never spoke of D Day. A notable exception to Tom's no-talk rule was when he hosted a visit from a group of Wellington College pupils in 2012. He talked them through his D Day experience with maps, bringing it vividly to life. The teacher who brought them wrote "It was a memorable day for us, and it was an honour and a privilege to be with you all then. Tom was terrific, energy and enthusiasm unbounded and with an extraordinary recall of D-Day and events of that time."

The people who shared this experience were an important part of Tom's life. Once he returned from overseas, he attended the Royal Engineers all ranks D Day reunion each year into his eighties, by which time only a handful were well enough to attend.

We are grateful to his sister Mary, who insisted that he write these recollections.

References

- Extracts from Tom Marsh's Personal Recollections 2011

- C1 Cdn Para Bn Association Archives.

https://www.academia.edu/103180335/A_Most_Irrevocable_Step_Canadian_Paratroopers_on_D_Day_The_first_24_hours_5_6_June_1944 - https://www.inthefootsteps.com/dday_part_21.pdf

- © C.P. Stacey, The Victory Campaign, Sketch 6